Poker & Pop Culture: Card-Playing Cowboys in American Westerns

In the history of film criticism, the western holds a special place. The western really is the start of "genre criticism" in film �� that is, that variety of analysis and interpretation that foregrounds audience expectations created by the way a film's narrative and thematic elements resemble other, similar films.

Because there were so many westerns made during the silent era and the first decades of sound film (up through the 1960s), these formal �� or formulaic �� similarities became readily apparent from film to film. Indeed, it was around the 1960s �� when westerns started to be made less frequently �� that "genre critics" would use westerns as a kind of starting point for talking about genre itself.

There are many reasons why westerns were so popular. Most were set during the period following the Civil War, starting with the Reconstruction and last up through the end of 19th century and period of continued westward expansion. While particular western films occasionally ignite debates about historical authenticity, many agree that the majority of westerns present a relatively idealized version of the Old West, often highlighting certain ideological values and ideas of national identity that helped make the films more commercially popular (as is often the case with mass market entertainment).

In other words, these fictionalized accounts of the past were often presented with an eye toward satisfying contemporary audiences' most favored ideas of themselves and of America. To overgeneralize a bit, most westerns of the first half of the 20th century (and into the 1960s) present an uncomplicated view of American progress and achievement, with the advancement of the frontier �� the "victory" of civilization over wilderness �� being championed.

There were exceptions that challenged such positive or "romantic" versions of history �� The Searchers (1952) springs to mind as a good example of a western highlighting white settlers' harsh treatment of Native Americans. And latter-day westerns (late 1960s and after) very often problematize such idealized notions of cowboys and their stories �� The Wild Bunch (1969), set a little later during the 1910s and depicting a group of outlaws who uncomfortably seemed to have outlived their era, is often regarded as a kind of turning point for the genre.

Setting aside these ideological concerns, I wanted to focus on one narrative element typical of the "classic western" such as was made from the 1930s through the 1960s �� namely, the inclusion of poker.

In some westerns, the use of poker is merely ornamental. That is to say, having characters play the signature card game of the Old West is akin to making sure characters wear Stetson hats, ride horses and carry guns. It's part of the requisite scenery, like the vast landscape shots typically serving to segue the plot from one scene to the next.

However, there are many examples of westerns that took greater care to incorporate poker more significantly into their plots, including several instances of filmmakers consciously evoking thematic emphases in their poker scenes. In some cases, westerns retelling the stories of poker-playing historical figures like Will Bill Hickok, Doc Holliday and Bat Masterson necessarily pushed poker into the foreground. However, there are several other instances of Westerns that thoughtfully incorporate poker not just as a casual reminder of the Old West setting, but as an important element of the storytelling.

Over the next couple of columns I'm going to present a short survey of a half-dozen classic westerns that ably "use" poker as more than just a way to carry the viewer from an early argument in a saloon to a climactic duel in the dust outside. Rather, in these films poker has a thematic significance, helping reflect something important about the characters, the larger messages of the film or both.

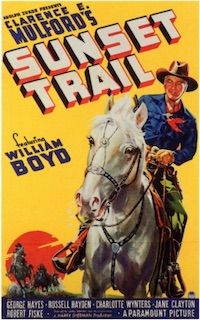

Sunset Trail (1939)

One of the early wave of what would eventually be more than 60 films featuring the character of Hopalong Cassidy, Sunset Trail is exceedingly formulaic with its presentation of the justice-seeking cowboy foiling a villainous plot, in this case one perpetrated by a lawless casino owner.

In the original stories written by Clarence E. Mulford just after the turn of the century, Cassidy was a rough-hewn wrangler, but in the films he is transformed into a comically-chaste iconoclast who doesn't smoke, avoids hard language and only drinks sarsaparilla. The character kind of pokes fun at "masculine" traits associated with cowboys, but ultimately reinforces those traits by showing it's mostly an act and Cassidy is as tough as they come.

William Boyd had already starred as Cassidy in more than 20 films (produced in just four years) by the time he appeared in Sunset Trail, meaning audiences were well acquainted with the character's idiosyncracies as he inevitably triumphed over whatever criminal behavior he encountered.

The film begins with Silver City Casino owner Monte Keller (played by Robert Fiske) purchasing a ranch and 2,000 head of cattle from a local farmer, paying him $30,000 in cash. Keller then shoots the farmer as he leaves town with his family, reclaiming the money and forcing his victim's wife and daughter to have to return to Silver City to start their lives anew.

Eventually Cassidy arrives to save the day, though comes disguised as a dandy with seemingly little experience riding horses and other ways of the Old West. He even responds with mock disgust at the sight of the casino.

"Gambling... tsk, tsk, tsk," he says upon meeting Keller and learning his business. Even so, he ends up visiting the establishment more than once to "give Dame Fortune... a whirl," eventually piecing together that Keller has killed the farmer after playing faro and winning a bill bearing a serial number from one of the stolen notes.

But rather than simply calling in the law to settle matters, Cassidy (still in his dandy character) plays a game of high-stakes stud poker with Keller. In the game he continues to act the part of a greenhorn, pretending to be ignorant of poker strategy or terminology. At one point he requests a "new bunch of cards," not aware it is called a "deck." When asking that they play with cash rather than chips, he says "I don't like those silly things... I can never keep track of the colors."

In one big hand of five-card stud, we see Cassidy showing 2?9?9?2? versus Keller's 7?5?Q?4?, then leading for $100. Keller raises to $500, and Cassidy sits up.

"Oh, you've got a...." He trails off before rechecking his hole card. "Oh, I wish I could remember... two pair... three of a...." He looks around.

"Does a full house beat a flush, do any of you gentleman know?"

Keller looks menacingly, preventing anyone from answering, then watches Cassidy raise to $1,000.

"Awww... take it," says Keller as he folds, turning over his hole card �� the A? �� as he does. Cassidy then reveals his card �� the 8?!

"Oh, I'm so sorry," he says. "I thought that was a nine."

The scene is well-managed, actually, and while Cassidy's faux fumbling about Silver City might be a little tedious at times (to this viewer), the poker game neatly functions as a kind of miniature set piece mimicking the larger plot of Cassidy successfully bluffing Keller into "losing" the more serious game he's playing.

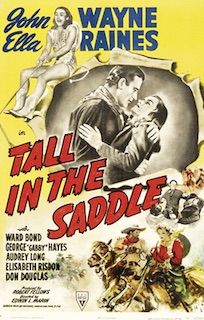

Tall in the Saddle (1944)

This John Wayne vehicle is a fast-paced and entertaining western containing most of the elements one finds in "horse operas" of the era, with a complicated plot punctuated by stage coaches, saloons and shootouts. It also includes poker in an early scene that introduces how Wayne's character, the independent Rocklin, represents the keeper of order amid the lawless Old West.

We first meet Rocklin arriving at Garden City by train, then catching a coach to Santa Inez. The driver, Dave, is played by frequent sidekick George "Gabby" Hayes (who also has a supporting role in Sunset Trail, incidentally). He drives Rocklin �� or "Rock," as Dave calls him �� and others to the city, and they engage in conversation along the route. One topic they discuss is Dave's boss, Harolday, whom he dislikes.

"He's too darn sane, believing in law and order," says Dave of Harolday between swigs of whiskey. "What's wrong with law and order?" asks Rocklin. "Well, it depends on who's dishing it out," answers Dave. "I never was much on taking orders myself, and as for the law... heh... you'll find out what that means around these parts."

Soon after arriving in Santa Inez, Rocklin joins a poker game at the Sun-Up Saloon. The game includes several players, including Clint Harolday (Russell Wade), the stepson of Dave's boss, and another named Judge Garvey (Ward Bond). Clint has been winning, they warn Rocklin, and soon enough he and the young gun get involved in a contentious hand of five-card draw.

After the deal, Rocklin opens for $3 and Garvey folds. Clint then raises to $20, forcing the others out. "Call you for six," says Rocklin, referring to the last bills he has left on the table. "Dig," says Clint, indicating Rocklin should go into his pockets to produce enough to call the raise.

Garvey reminds Clint they are playing table stakes, but Clint objects. "Not if he wants to dig," he sneers, and Rocklin does just that, saying "I got you beat" as he puts out the money to call.

Each player then draws one card, with the card delivered to Clint �� the Q? �� being accidentally exposed. He quickly picks it up and fits it into his hand, grinning widely as he does.

"That queen is dead," says Rocklin evenly. "I can take it if I want it," Clint responds. "Sure, if you want," says Rocklin, still calm. "But you gotta beat my hand with four cards," he adds. "I'm playing these mister," says Clint defiantly, ignoring Rocklin's insistence upon the rule regarding the exposed card.

There's a pause as they look around at the others, and Judge Garvey suggests they consider splitting the pot. "I'm not splitting," says Clint with a smile. "I'm betting." He then puts the remainder of his stack of bills in the center. "You calling?"

"Nope," says Rocklin, and Clint begins to reach for the pot. Then Rocklin interrupts him. "I'm raising," he says, putting the rest of his money forward. Clint's face droops.

"Dig," says Rocklin.

Clint asks another player for more money, but when he refuses Clint says "I've called for all I've got" and turns over his hand. "Full house," he says proudly, but Rocklin ignores him.

"Kings up win," says Rocklin, referring to his hand. "That third queen is dead."

As Rocklin starts to drag the pot, Clint rises up and draws his pistol. "Get away from that table and get out of here," he says. "Maybe from now on you'll know a full house beats two pair, you four-flusher."

Rocklin quietly leaves, walking up the stairs to his room above the saloon. As Clint gathers the money, it is reiterated to him how the exposed card was in fact dead.

"When anybody plays poker with me they play my game or not at all," says Clint. They warn Clint that Rocklin is coming back, but he doesn't believe it. But of course, Rocklin returns, now sporting a full holster.

"I've come for my money," he says, and Clint immediately relents. "Sure," he says quickly. "I guess I was wrong about that queen," he continues, but Rocklin isn't listening. Instead he deliberately gathers the bills and bids the men good night.

The scene confirms Dave's earlier observation about "law and order." There are rules, sure, but not everyone cares to follow them, and ultimately what really matters is whether or not someone is willing and powerful enough to enforce the rules.

The scene also importantly positions Rocklin as willing to take on the responsibility, which, as you might imagine, becomes very needful once he gets more deeply involved in the ranch wars happening in Santa Inez. Indeed, it precisely foreshadows the larger story, with Rocklin being the one having to bring order to the anarchic Old West town.

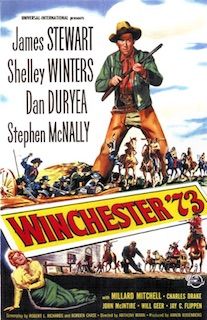

Winchester '73 (1950)

Finally the 1950 film Winchester '73 is in some ways an unusual western, although it still fits snugly within the category as it features easy-to-identify heroes and villains with good winning out as expected in the end.

As the title suggests, some of the weapons used during the Old West take center stage, with the Winchester Rifle Model 1873 �� a.k.a., the "One in One Thousand" �� being the most coveted weapon among good and bad alike.

The story opens on a shooting competition held in Dodge City where Marshal Wyatt Earp (played by Will Geer) keeps the peace in part by refusing to allow anyone in the city to carry a gun. Two shooters emerge as the finalists, Lin McAdam (Jimmy Stewart) and Dutch Henry Brown (Stephen McNally).

As it turns out the two men have a long history of bad blood between them. It's later revealed Dutch Henry killed McAdam's father, and during the story's climax �� spoiler alert �� we learn the pair are actually brothers, meaning the man Brown killed was his father, too.

Lin wins the competition, but Dutch Henry and his gang beat him up and make off with the prized Winchester, leaving town without retrieving their other weapons and therefore putting themselves at risk amid surrounding tribes of Indians. (The story is set just a couple of weeks after the famed Battle of Little Big Horn, a.k.a. Custer's Last Stand.)

Soon Dutch Henry stops at Riker's Bar where a trader named Joe Lamont (John McIntire) happens to be along with a stockpile of weapons. Dutch Henry tries to buy some guns with the $80 he has after eating a meal, but spying the "One in One Thousand" Winchester Lamont says he'll only trade his weapons for it.

When we first see Lamont he's shuffling a deck of cards, and rubs an ace of spades in a way that suggests it might be marked. He then plays solitaire, but Dutch Henry suggests a game of poker as a way to try to bolster his low funds.

"I'm not much at poker myself," pleads Lamont, although we soon see it is a ruse not unlike the one Hopalong Cassidy pulls in Sunset Trail as Lamont cleans out Dutch Henry. Whether Lamont is cheating or not isn't made explicit, although it appears a likely possibility.

A frustrated Dutch Henry sells Lamont the Winchester for $300 with which to continue playing, and on the first hand is dealt a pat full house �� A?A?A?8?8?. He immediately bets all of it before the draw (no sandbagging here!), and Lamont calls the shove before drawing a single card. Then comes the showdown.

"Aces full on eights," says Dutch Henry proudly. "Just missed being a dead man's hand."

"Not enough," replies Lamont. "Four treys."

Again, we don't know if Lamont has cheated, but the unlikelihood of such hands makes it seem as though Dutch Henry isn't just being particularly unlucky.

Moving ahead to the film's conclusion, the gun has transferred hands a few times before Dutch Henry has it back, and as expected he ends up in a climactic shootout with Lin, his brother. Dutch Henry shoots erratically and often, and amid the gunfire Lin brings up their father and his lesson not to waste ammunition.

"The old man told you never to waste lead," yells Lin. "Now you're short."

Despite having such a high-grade weapon, Dutch Henry isn't handling it well �� not unlike the way he overbets his aces full of eights, or (perhaps more accuarately) the way he recklessly fails to notice Lamont is hustling him. In any case, his status as one destined to lose such heads-up confrontations is reinforced by the poker game.

To these westerns the scenes add color and often a kind of respite between action sequences that lends variety to the narratives. But as noted, in many instances they also help reinforce larger ideas about characters and thematic emphases.

From the forthcoming "Poker & Pop Culture: Telling the Story of America's Favorite Card Game." Martin Harris teaches a course in "Poker in American Film and Culture" in the American Studies program at UNC-Charlotte.